Gay Talese's High Notes

There’s an opening in journalism today for writers who know how to tell a story. Any hack can record the facts, but it takes a special someone to report with their nose to the ground and weave a tale of their findings while remaining accurate in their assertions, portrayals and quotes. Though the age of New Journalism - where writers churned out longform pieces guided by these principles, financed by large magazine and newspaper budgets now trimmed to a fraction of their former size - is gone, works from this era still provide hints to serious students about how to hook readers. The principles of New Journalism can apply to shorter articles, and if no other writers are up to the task, I’ll lead this renaissance myself.

Gay Talese already did that, though. Of New Journalism’s standard bearers, Talese is one of the medium's most individualistic voices. In his latest collection High Notes, a retrospective of Talese’s best magazine reporting, his vaunted position is rightfully asserted. Short pieces like “Four Hundred Dresses” detail the proclivities of famed New York society figures, like Elaine Kaufman who owned Elaine’s on the Upper East Side until her death, a restaurant that earned reference in places as diverse as Renata Adler’s 1976 riveting, discombobulated novel Speedboat to Billy Joel’s in-your-face 1979 hit “Big Shot.” “Four Hundred Dresses” detailed Kaufman’s bespoke wardrobe - all her dresses were made by one Linda Meisner, four hundred in all based on two distinct patterns. Though the piece is barely one thousand words long, Talese draws readers in with the detailed idiosyncrasies of Kaufman’s character, which make it easy to imagine why Elaine’s made a lasting blueprint on the New York social scene during its 48-year run. “Four Hundred Dresses” resides among other classic pieces like “Frank Sinatra Has A Cold.” Talese’s profile on Ol’ Blue Eyes reads as an entertaining character analysis or a gripping novella, and he managed to attain and verify all the information without speaking to Sinatra himself even once. This process is detailed in the following piece, “On Writing “Frank Sinatra Has A Cold,”” which gives readers a peek into the method behind Talese’s madness. “Wartime Sunday,” Talese’s encounter with Joe DiMaggio in an old school Italian joint in Atlantic City, where he found that DiMaggio ate his spaghetti the wrong way (with a fork and spoon) makes a requisite appearance, starting off the series of stories as one of Talese’s earliest pieces. High Notes ends on its namesake article, a 2011 piece from The New Yorker where Talese detailed a recording session between Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga. The duo performed a rendition of “The Lady is a Tramp” for Bennett’s album Duets II, which they recorded nearly ten times because they were having so much fun nailing each take, aided with a few sips of whiskey on Gaga’s part. It’s a high note for the book to end on indeed.

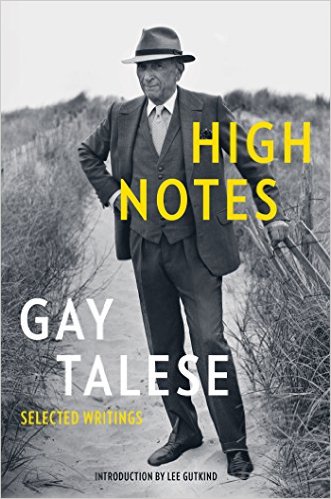

Beyond his writing, Talese is also a style icon. He wears a suit everywhere, every day. Readers first learn this when looking at the cover, where Talese stands on a sand dune, his leather shoes sinking as he holds on to a fallen fence post. Talese is perhaps the only man daring enough to wear a three-piece suit - and he’s always in a three-piece suit - to the beach, as well as observe classic rules of formality surrounding headgear. Rare is a photo of Talese bear-headed, and his signature wide-brimmed fedora is a dapper top-off to his formalism of a distant age. Further research uncovers images of Talese in other beautiful suits, and in a recent video for GQ Style, he shows Will Welch (the publication's editor) around his Upper East Side townhouse while wearing a resplendent royal blue suit, a blue and white striped shirt with a crisp, contrasting white collar, a yellow foulard tie, a floral red and white pocket square and - in select shots - a cream fedora. Throughout the video we see some of Talese’s other suits, including a gorgeous three-piece tobacco-colored number, white double-breasted suit with black pinstripes and a tan sportcoat with kodiak brown suede piping, sewn on by a masterful tailor to replace aging lapels. If Talese’s incredible wardrobe doesn’t make you want to try bespoke tailoring at least once, then nothing will. Furthermore, Talese lets viewers on to why he dresses so well; he believes every moment we step outside is an occasion. In his words, “It depends on when I wake up, what the day looks like. I see the sidewalk from my window, and I see myself as a pedestrian.”

On the eve of High Notes’ publication, Talese was mired in the most direct attacks on his reputation in years. Last April, he made the mistake of commenting during a Boston University conference that there were no women writers who had inspired him, thus subjecting himself to the fury of Twitter. In Talese’s defense, there were few prominent women journalists when he was growing up in the 1930s and ‘40s, so part of his tongue-slip is due to differing generational mores. Soon afterward, the veritability of his 2016 book The Voyeur’s Motel was diminished after the main source was found not to be credible soon before its publication. Talese disowned the book, though from an initial glance at a bookstore, the prose holds up and it could be the 2010s equivalent of James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces - an entertaining read despite the work’s discreditation. Upon High Notes’ publication, however, these misgivings have been brushed under the table, and Talese remains in his rightful position as one of the greatest journalists of the 20th and 21st centuries.