Postscript: Chuck Berry

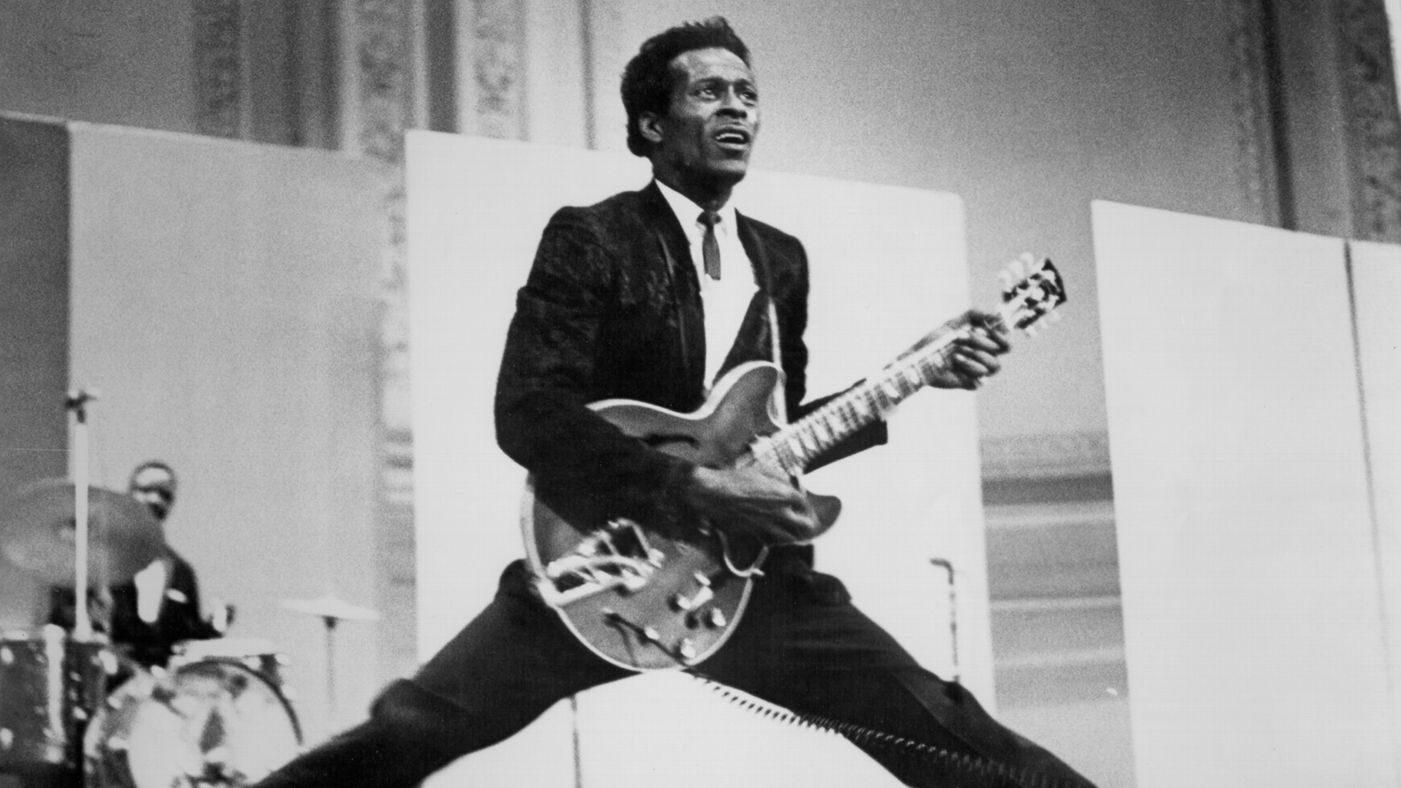

I rarely listen to Chuck Berry’s music but I hear it all of the time. In every stripped-down two-chord rock and punk tune is a little bit of Berry's sound. Pick a tune by the Rolling Stones or the Yardbirds, and there are riffs and fragments borrowed from Berry’s musical vocabulary. For anyone who claims Elvis invented Rock ‘n’ Roll, they’re wrong. He learned his moves from Berry, who sped up classic blues motifs and married them with the twangy guitars of country music. The kids responded and the crowd went wild for his danceable, suggestive tunes. As Berry himself put it, “It’s got a backbeat you can’t lose…”

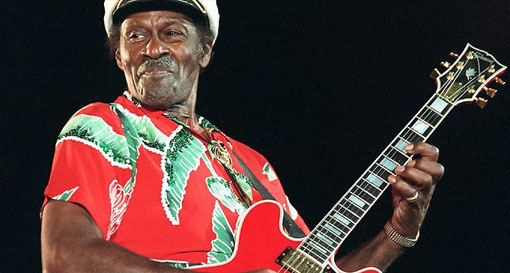

Berry passed away last Saturday, safely enshrined in the pantheon of rock legends, past and present. At the ripe age of 90, he had planned to make another album. Whether or not we’ll ever get to hear what he completed remains unknown. What we do know, however, is that anyone with the moxie to set out making another album at 90 is someone who’s done enough to further American music that one more go-round doesn’t put their reputation at risk.

Born October 18, 1926, Berry was one of the last living Rock ‘n’ Roll musicians of yore. He hit the scene in 1955, with the single “Maybelline,” which he cut for Chess Records out of Chicago. A subsequent string of hits followed - from “Roll Over Beethoven” to “Rock and Roll Music” and “Johnny B. Goode” - as well as several criminal charges and prison sentences, including a 1961 conviction for violating the Mann Act and transporting an underage girl across state lines. Berry wasn’t a bad man, however, but a Rock ‘n’ Roll renegade who never lost his touch during these interruptions. His 1964 hits “No Particular Place to Go” and “You Never Can Tell” are proof he didn’t lose his touch while incarcerated. The thumping country-flecked bass line and guitar solos of these tunes sounded like the best of Berry’s work from the late 1950’s. Though Rock ‘n’ Roll soon gave way to psychedelic sounds and weighty themes, Berry’s lyrics hadn’t lost their luster since they still depicted the anxieties and excitements of American youth.

Berry’s star cooled in the late 1960’s, but experienced a brief resurgence in 1972 with his salacious single “My Ding-A-Ling,” a blatant double entendre recorded live in London. “Ding-A-Ling” proved Berry was a musician’s musician, even when tested with a novelty tune. There was nothing Rock ‘n’ Roll in “Ding-A-Ling’s” melody - minus its simplistic strumming - yet its subversive, sly naughty humor possessed rock’s suggestive edge. Though the audience roars with laughter at some of the lyrics, Berry never loses composure throughout the song’s 4:18 duration. And while it only launched a momentary renaissance for Berry’s popularity, it proved his versatility and cemented his unimpeachable musicianship.

Though Elvis defined Rock 'n' Roll's star power, it’s time - posthumously - for Berry to reclaim the throne as his own. His influence is found everywhere from the gritty two-chord melody of Iggy Pop’s “The Passenger” to the catchy youthful infatuation of the Romantics’ “What I Like About You,” which Berry once said in an interview “Sounds a lot like the sixties with some of my riffs thrown in for good measure.” The Rolling Stones wouldn’t have existed without Chuck Berry, and Mick Jagger eulogized him on Twitter, revealing “He lit up our teenage years, and blew life into our dreams of being musicians and performers.” With his two-chord melodies done up in sprightly yet snarling major motifs, he helped create the language and blueprint for a genre of music that’s spawned numerous subgenres to this day. And with Berry on lead vocals, if there is a Rock ‘n’ Roll heaven then, according to the Righteous Brothers, “You know they’ve got a hell of a band.”