Stay Curious: In Defense of the Flâneur

I am a curious person and a born researcher. I roam the streets looking for inspiration, and perhaps angling for the elusive street style shot that hasn’t been pointed at me - yet. Because of this, some might call me - and men of a similar ilk - dandies. The modern connotation of “dandy,” however, is pejorative. To be “dandy” in this day and age is charmingly, disarmingly old fashioned. To be “a dandy” in modern times is a sign of overcompensation.

It was Glenn O’Brien who, through his writing, introduced to me - among many other things - the concept of the flâneur. In his book How to Be a Man, O’Brien noted that “I’ve been called [“flâneur”] a couple of times lately in blogs, and I like that, but I think I work too hard for it to be a perfect fit.” In one of the few instances where I disagree with him, O’Brien settled on the term “dandy” as a descriptor for the stylish man-about-town, the person who cultivates their look through both observation and studiousness. In the sense that style is the result of engaging with such curiosities, flâneur will do.

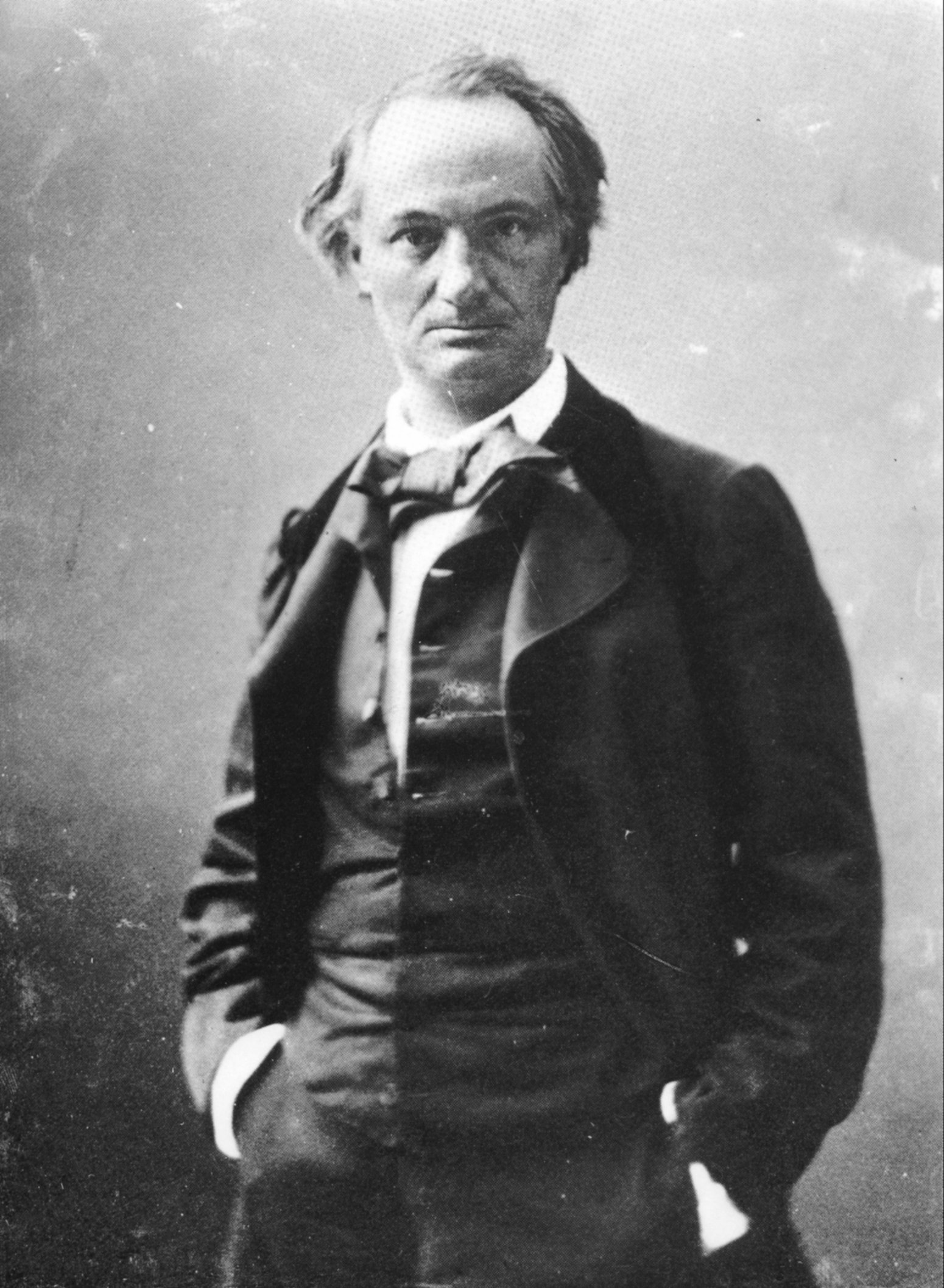

Charles Baudelaire.

There are many issues with the dictionary definition of flâneur, no doubt. According to Merriam Webster, a flâneur is “an idle man-about-town.” The problem with this definition is the meaning of idle, a synonym for laziness and unemployment, depending on its usage; either way, it’s not a compliment whatsoever. It’s this definition which O’Brien takes umbrage to, and rightly so. But it’s not this connotation of the flâneur that best describes the well-heeled modern man, keenly aware of his surroundings, who’s curious and observant toward everything he sees, touches, reads, listens to and experiences.

Consider the 19th-century French meaning of flâneur, which carries on today thanks to the resurgent popularity of literary critic Walter Benjamin. Benjamin wrote extensively on the flâneur since he was fascinated and captivated by this character willing to see and experience everything based on innate curiosity and the time to experience. According to Benjamin, the flâneur “was a figure of the modern artist-poet, a figure keenly aware of the bustle of modern life, an amateur detective and investigator of the city, but also a sign of the alienation of the city and of capitalism.” One could argue, perhaps, that the creative class is composed entirely of flâneurs. Sure, creatives work harder than the flâneurs of yore, but they share the quality with the 19th-century French flâneur where their work is play, where they are supremely engaged while exuding a sense of leisure in what they do. And while the flâneur isn’t always a creative, they engage with the essence of creativity, which is to know of their surroundings, the places, spaces, things and trinkets that make up their lives (and for the modern flâneur, to document it in some way, preferably on Instagram).

The things you find when you stay curious.

In the introduction to Benjamin’s Illuminations, philosopher Hannah Arendt described how his mode of writing - and penchant for collecting - mimicked the root of flânerie. Arendt wrote, “Still, they are striking examples of the flânerie in his thinking, of the way his mind worked, when he, like the flâneur in the city, entrusted himself to chance as a guide on his intellectual journeys of exploration.” Herein lies the beauty of the flâneur - in a society dominated by technology, obsessed with “getting things right,” flânerie is the opposite, the antidote to the illness of hyperconsumption that suppresses the natural curiosity in all of us. When the flâneur wanders through the city, they take their time and stop to marvel at the everyday because they find something extraordinary in the faded glory of an old building or the loving patina on a classic car, to name a couple observations the average person misses. The flâneur notices the style around them (not just on the internet) and thinks - based on what catches their eye - “I want to know more about this style because I saw it worn well and I want to pull it off, too.” The flâneur wanders in and out of wherever piques their curiosity, not merely popping in at a shop or a café because some trendy magazine declared it as a place to see and be seen. Sure, the flâneur’s raison d’etre is to see and be seen, but on their own terms; they see what they want to see, and will be seen by those in the know.